background, text and translation

Background: Gustaf Düben & Dietrich Buxtehude

Everything about the genesis, destination and performance of the cantata cycle Membra Iesu nostri is shrouded in mists. Only the title page lifts a corner of the veil: A year (1680) and a destination: Gustaf Düben (1628-1690), chapel master at the royal court of Sweden (Stockholm), scion of an aristocratic Swedish family of musicians, passionate music collector. He collected more than 2,500 compositions from all over Europe. In 1732, his son donated it to Uppsala University where it still resides: the Düben Collection, a true Fundgrube for the music lover. Many compositions (by Schütz, Carissimi, Du Mont, Krieger, to name but a few) are only known today because Gustaf copied them at the time. The undisputed primus in the Düben collection is Dietrich Buxtehude (ca. 1637-1707) with no fewer than 105 compositions. Were it not for this collection, we would put the North German (better: Danish) musician Buxtehude away as an organ virtuoso, forerunner and inspirer of J.S. Bach. Thanks to the Düben collection, we get to know the same Buxtehude as a composer of finely crafted spiritual music: German and – to a lesser extent – Latin motets, concertos. That was not his ‘job’. It is not even certain if that music ever sounded in Lübeck. The masterpiece of this collection is the seven-part cantata cycle on the ‘Suffering Christ on the Cross‘, Membra Iesu nostri.

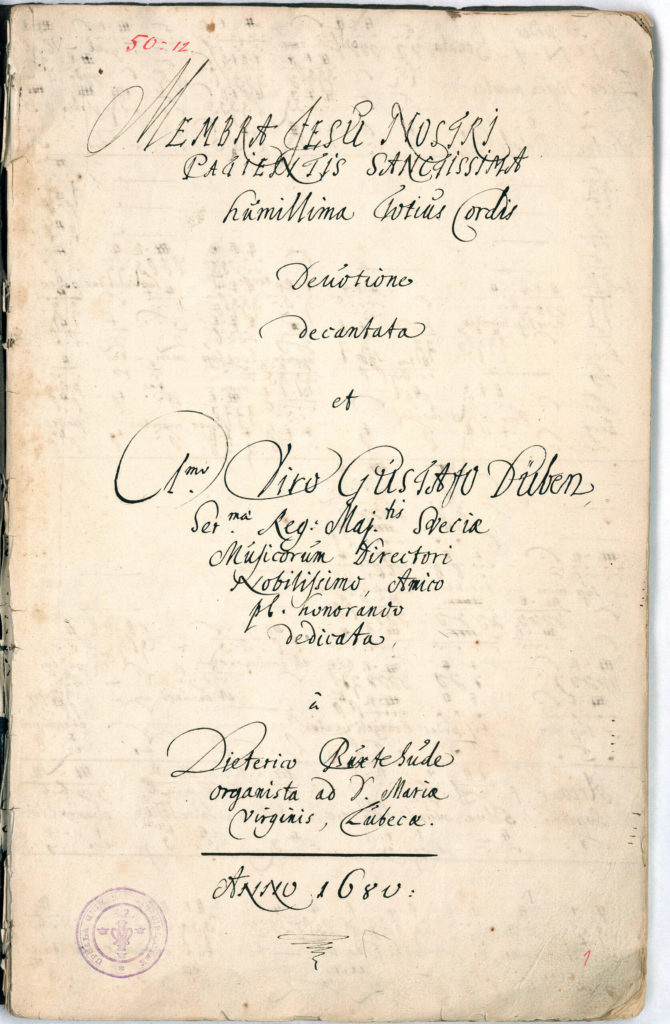

It is rewarding to read this autograph title page written by Buxtehude:

MEMBRA JESU NOSTRI | PATIENTIS SANCTISSIMA | humillima Totius Cordis | Devotione | decantata | et | 1.mo Viro GUSTAVO Düben | Ser[enissi]ma Reg[ia] Maj[esta]is Sueciæ | Musicorum Directori | Nobilissimo, Amico | pl. Honorando | dedicata | à | Dieterico Buxtehude | Organista ad S. Maria | Virginis, Lübeck. | ANNO 1680:

The very sacred members (body-parts) of our suffering Jesus

in humble reverence wholeheartedly

sung,

and

To the eminent Lord Gustaf Düben, music director of his most august majesty the King of Sweden,

[my] very noble and honourable friend,

dedicated,

by

Dietrich Buxtehude, organist at the church of St. Maria Jungfrau in Lübeck.

In the year 1860.

The cycle is thus dedicated to Gustaf Düben. Out of friendship, homage, or by request? We do not know. The liturgical setting is also unclear. The most obvious is to think of ‘performance in private circle of/for/by enthusiasts’. Such ‘pious music groups’ could certainly be found in Germany and Sweden. Did Buxtehude perhaps also have contact – in addition to his work – with such mystical-musical groups? We don’t know, but the question does arise. Düben made vocal books from the tablature Buxtehude sent him and thus performed the works, probably in ‘Holy Week’, perhaps by analogy with the ‘dark metts’ that were so popular in south-western Europe: the Tenebrae.

The text: Salve mundi salutare

The text of the arias (the central part of each ‘cantata’) was chosen from an early 13th-century poem: Salve mundi salutare [Hail, saviour of the world], a long prayer cycle intended for the monks of the Cistercian abbey of Villers. Abbot Arnulf of Leuven (died at Villers in 1250) wrote these prayers as a spiritual exercise when contemplating Christ crucified. It breathes the spirit of the personal Christo-centric spirituality of Bernard of Clairvaux. For a long time, this metrical prayer (oratio rhytimica) was also attributed to him, but the discovery of an old manuscript written by a monk from Villers, destined for the nunnery Vrouwenpark (Wezemaal) assigns the text to Arnulf.

More about this hymn

A guided meditation

It is a guided meditation with a high poetic content and a complex rhyme scheme aabbc/eeddc, highly innovative for the time. In it, Abbot Arnulf urges his ‘children’ (monastics) to kneel – e.g. on Good Friday – in front of an image of the crucified (a crucifix), and then empathise with Christ during the Passion. Not out of morbid sensationalism or masochism, but to appropriate (make own) the meaning of that suffering: This was done to save the world (me). Besides being the cause (causa = propter nos) of Christ’s suffering, man is also its goal (finis = pro nobis): to save him (salutare, salus). Salve is not for nothing the key word of this prayer, which begins with Salve (greetings, salvation) and ends with salutifera (salvation). This makes the pious contemplator humble and grateful; it humbles and exalts, hurts and gives joy. Christ dying creates life. It is these great paradoxes of the Christian religion that animate the text: Bittersweet thus becomes Jesus’ remembrance.

A guided meditation, also literally: from bottom to top: You kneel before the crucifix, focusing attention first on the feet, then the knees, then the arms and the wound in the side. To end at the head via the chest and the heart (inserted later – 14th/15th century – metrically unstable, and many duplications): the violated face. These are the seven membra Iesu nostri. The concrete physical images evoked by this contemplation are filled with meaning and sense via theological imagination, which then descends into the soul of the contemplator via the poetic power of the oratio rhytmica.

This cycle has become a seminal text of Christianity, in countless manuscripts scattered all over north-western Europe, and after the split in the Christian church (also known as the Reformation) has remained popular as a meditation text in both parts of it. There are translations of it in the vernacular (as early as the Middle Ages) and Paul Gerhardt, among others, reworked the entire text into 7 songs. You know his arrangement of the last part: ‘O Haupt vol Blut und Wunden‘ a faithful transcription of Arnulf van Leuven’s last cycle of prayers. You will also easily recognise that other stanza from the St Matthew Passion: Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden (‘Dum me mori est necesse’, cantata 7, aria 2).

Buxtehude’s setting

When Buxtehude composes music to this selection, he has each of these prayers introduced by a sonata. This sets the tone, literally. Then follows a biblical verse (set to music in the form of a concerto). In it, for the good listener, the meaning of the cycle is revealed. So you will hear the joy that precedes the first meditation. And the stillness when it comes to the knees on which the suffering man may rest, as with a mother. Yes, the image of God in the 13th century was more than just masculine. And in the movement ad manus (the hands), Buxtehude shows the pain in the concerto in a very classical way, how it teeters and chafes (at the word Plagae). The arias themselves are rather ‘sec’ in tone, but make no mistake: the expression of the content and the intended affect are there. You will hear it, as the heart begins to beat when touched by Jesus’ heart. Each of the seven movements concludes with a repeat of the concerto, except for the seventh movement, which concludes with an ‘Amen’. This creates the following basic scheme

- Sonata (instrumental)

- Concerto (biblical text – often performed by a choir, but can also be performed solo)

- Aria (three times over an equal bass, changing instrumentation)

- Concerto (repetition of 2)

Exceptions to this scheme: In cantata 1, the reprise of the concerto (no. 4) continues with a polyphonic repetition of the first verse of Salve mundi salutare. In cantata 7, instead of the repetition of the concerto, a grandiose Amen follows. Meanwhile, starting in c, Buxtehude has walked the circle of fifths (in minor: c-g-d-a-e) to end in c-minor [note: the second cantata is the odd one out: it is in major third: E-flat]). In the tablature, a director’s note at the end of the 6th cycle betrays that Buxtehude did indeed think of a continuous performance: indeed, it says at the bottom of the page: ‘Volti, ad faciem’ (= turn page for Ad faciem).

The cycle is thus – musically – a whole, while at the same time each part is a complete cantata – and can be performed separately (which, according to the vocal books Düben made of it, may have happened in Sweden).

Mysticism

One more thing: Until well into the 20th century, it was quite common to attribute hidden meaning (allegoresis) to nature, and all kinds of biological and physical phenomena. Every détail of Jesus’ suffering could become a sermon in itself. We have forgotten that. For instance, it might be difficult to follow how the ‘wound in Jesus’ side’ can at the same time be the source of life, a place of refuge from the ‘roaring lion’ (= devil), like ‘a dove in a cave in the rock face'(from Solomon’s Song of Songs, applied to the bond of love between Christ and believers). Below the text, I have explained some of the issues. NB: This complex and ramified network of hidden meanings also plays a crucial role in Bach’s Passions and cantatas and has left its mark on Arnulf van Leuven. In the Matthew Passion, for example, when the viewer sees Jesus’ hands nailed to the cross, his mind fills up and he exclaims Sehet, Jesus hat die Hand, uns zu fassen ausgespannt, exactly the same double reaction as in stanza 1 of cantata 3 (ad Manus): it is horrible what is happening, but this is how God expresses his love to me: bittersweet is Jesus’ memory.

Dick Wursten

Performance by René Jacobs c.c.

Translation (Dick Wursten, 2024)

Cantate I — Ad pedes

(the feet)

Ecce super montes pedes evangelizantis et annunciantis pacem.

Behold upon the mountains the feet of him that bringeth good tidings, and that preacheth peace (Nahum 1,15 [2,1])

| Salve mundi salutare. Salve salve Jesu care! Cruci tuae me aptare Vellem vere tu scis quare; Da mihi tui copiam. | Hail, the world’s salvation Hail, dear Jesus, I want to cling to your cross I really do, you know why. Help me to achieve it. |

| Clavos pedum, plagas duras Et tam graves impressuras Circumplector cum affectu Tuo pavens in aspectu Tuorum memor vulnerum. | The nails in the feet, terrible wounds, so deeply driven into the flesh, I encompass them affectionately and I tremble, at the sight of you, because I remember your wounds. |

| Dulcis Jesu, pie Deus Ad te clamo licet reus Praebe mihi te benignum Ne repellas me indignum De tuis sanctis pedibus | Sweet Jesus, good God to you I plead, guilty as I am: show yourself to me in goodness and do not reject me, unworthy, from your holy feet. |

A dual tone is set: a joyful beginning: the messenger of peace comes. His feet rush over the mountains…. but these are the same feet that are pierced on the cross: sweet joy (salvation) versus bitter suffering (guilt)

Cantate II — Ad genua

(the knees)

Ad ubera portabimini, et super genua blandientur vobis.

you shall be carried at the breasts, and upon the knees they shall caress you (Isaiah 66,12b)

| Salve Jesu, rex sanctorum, Spes votiva peccatorum Crucis ligno tanquam reus Pendens homo, verus Deus, Caducis nutans genibus. | Hail Jesus, King of the holy, hope, promised to sinners, on the wood of the cross just like a guilty man you hang, [and you are] truly God, quivering with weakened knees. |

| Quid sum tibi responsurus; Actu vilis corde durus? Quid rependam amatori Qui elegit pro me mori Ne dupla morte morerer? | What shall I give you in response, my actions vile, my heart hardened? How do I repay the lover who chose to die for me, to save me from the second death?* |

| Ut te quaeram mente pura Sit haec mea prima cura Non est labor nec gravabor Sed sanabor et mundabor Cum te complexus fuero. | That I may seek you with a pure mind, that be my first concern. It is no trouble and no burden, but it will heal and purify me, when I will have embraced you. |

* ‘Second death’: The idea behind this: The first death is the end of man’s natural life. The second death is when, at the Last Judgement, man is raised from the dead, and sent by God to the left (into hell).

Cantate III — Ad manus

(the hands)

Quid sunt plagae istae in medio manuum tuarum?

What are these wounds in the midst of thy hands? (Zecharia 13,6)

| Salve Jesu pastor bone, Fatigatus in agone Qui per lignum es distractus Et ad lignum es compactus Expansis sanctis manibus. | Hail, good shepherd, Jesus fatigated in agony, stretched out on the wood attached to the wood with your sacred hands widespread. |

| Manus sanctae, vos amplector Et gemendo condelector Grates ago plagis tantis Clavis duris, guttis sanctis Dans lacrimas cum osculis. | You holy hands, I embrace you, and lamenting (them) I am happy, I give thanks for these terrible wounds, the hard nails, the holy drops of blood with tears as kisses. |

| In cruore tuo lotum Me commendo tibi totum. Tuae sanctae manus istae Me defendant, Jesu Christe Extremis in periculis. | Washed In your blood I entrust myself completely to you: May these your holy hands defend me, Jesus Christ, in extreme peril (= death). |

* Classical ‘imagery’ that even in the ‘spreading of the hands’ of the crucified, sees an image of the Christ reaching out to the spectators at the foot of the cross: a blessing gesture. Compare St Matthew’s Passion: “Sehet, Jesus hat die Hand…“

** ‘washing in blood’ = cf e.g. Revelation 1:5 ’Jesus Christ, who loved us, and washed us from our sins in his blood.’ Revelation 7:14 ‘These are they who come out of the great tribulation; and they have washed their garments, and made them white in the blood of the Lamb.

Cantate IV — Ad latus

(the side)

Surge, amica mea, speciosa mea; et veni columba mea in foraminibus petrae, in caverna maceriae.

Arise, my love, my beautiful one; and come, my dove in the clefts of the rock, in the hollow places of the wall. (Song of Songs 2, 13-14)

| Salve, latus salvatoris, in quo latet mel dulcoris, in quo patet vis amoris Ex quo scatet fons cruoris Qui corda lavat sordida. | Hail, side of the Saviour, in which sweet honey is hidden, and the the power of love is revealed, from which bursts a fountain of blood that washes clean the soiled hearts. |

| Ecce tibi appropinquo Parce, Jesu, si delinquo. Verecunda quidem fronte Ad te tamen veni sponte Scrutari tua vulnera. | Behold, I approach you, spare me, Jesus, where I am guilty: with an embarrassed face I come to you, of my own accord, to explore your wounds. |

| Hora mortis meus flatus Intret, Jesu, tuum latus, Hinc expirans in te vadat, Ne hunc leo trux invadat Sed apud te permaneat. | At he hour of my death, let my breath/soul enter into your side, Jesus, and there breathe out into you, that the fierce lion may not invade here, but (my soul) will abide with you. |

The combination honey and love refers both to the Song of Songs, and to the riddle of Samson (book of Judges).

The side of Jesus as the source of the salutary blood of Christ, is general christian symbolism.

The side of Jesus as access to his heart is a mystical exercise, which has been linked to the preceding text of the Song of Songs, especially since Bernard of Clairvaux. Ditto for the side of Jesus as refuge.

Cantate V — Ad pectus

(the breast)

Sicut modo geniti infantes rationabiles et sine dolo [lac] concupiscite, ut in eo crescatis in salutem. Si tamen gustastis quoniam dulcis est Dominus.

Just like newborn smart babes, without guile, long [for milk], you must long to grow unto salvation. If so be, ye have tasted that the Lord is sweet.

(1 Peter 2, 2-3 first part adapted)

| Salve, salus mea, Deus, Jesu dulcis, amor meus. Salve, pectus reverendum, Cum tremore contingendum Amoris domicilium. | Hail, God, my salvation, sweet Jesus, my love: Hail, adorable breast, only approachable with fear, abode of love. |

| Pectus mihi confer mundum; Ardens, pium, gemebundum, Voluntatem abnegatam Tibi semper conformatam, Juncta virtutum copia. | Purify my heart that it will burn piously, full of sighs abnegating its own will evermore conforming to you connected with the fullnes of virtues. |

| Ave, verum templum Dei. Precor miserere mei, Tu totius arca boni ac electis me apponi, Vas dives Deus omnium. | Hail, you true temple of God, I pray: Have mercy on me, you ark* of all the good, let me be counted among the elect, you divine vessel**, God of all. |

* ark = ark of the covenant (OT), ark in which the sacrament is kept, Noah’s ark. You may choose, or better: you don’t have to at all. Playing with multiple simultaneous meanings

** precious vessel = image that our body is ‘precious vessel’ for the divine soul, occurs in the New Testament, and has only been reinforced by the marriage of theology and Greek (neo-Platonic) philosophy.

Cantate VI — Ad cor

(the heart)

Vulnerasti cor meum, soror mea, sponsa.

Thou hast wounded my heart, my sister, my spouse. (Song of Songs 4,9)

| Summi regis cor, aveto. Te saluto corde laeto. Te complecti me delectat Et hoc meum cor affectat Ut ad te loquar animes. | Heart of the Supreme King, greetings, I greet you with a joyful heart, grasping you delights me, and it touches my heart, so that you revive it to address you |

| Per medullam cordis mei, Peccatoris atque rei, Tuus amor transferatur Quo cor tuum rapiatur Languens amoris vulnere. | Into the marrow of my heart, – a sinner a guilty person I am – may your love be transmitted, so that your heart may be completely seized languishing by the wound of love. |

| Viva cordis voce clamo, Dulce cor, te namque amo Ad cor meum inclinare Ut se possit applicare Devoto tibi pectore. | Aloud, from my heart, I call out, sweet heart, for it’s you I love: Bend (your heart) towards my heart, so that it can applicate itself to you, to your revered breast. |

This section of the ancient hymn can only be understood if we are somewhat familiar with the devotion of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. This also suggests that this section is probably of a later date. The devotion was propagated by the Jesuits in particular, using this hymn among others. It is striking that it is maintained in the Lutheran version. The translation of the ending of the second verse is tricky (thus uncertain): ‘rapiatur’ can also be positive: your heart was raptured.

Cantate VII — Ad faciem

(the face)

Illustra faciem tuam super servum tuum; salvum me fac in misericordia tua.

Make thy face to shine upon thy servant; save me in thy mercy. (Psalm 30[31]:17)

| Salve, caput cruentatum, * Totum spinis coronatum, Conquassatum, vulneratum, Arundine verberatum Facie sputis illita. | Hail, bleeding head, fully crowned with thorns, shaken, wounded, beaten with a reed the face smeared with spit. |

| Dum me mori est necesse, Noli mihi tunc deesse, In tremenda mortis hora Veni, Jesu, absque mora, Tuere me et libera | If I have to die, do not abandon me; In the fearful hour of death come, Jesus, wiyout delay, protect and deliver me. |

| Cum me jubes emigrare, Jesu care, tunc appare, O amator amplectende, Temetipsum tunc ostende In cruce salutifera. | If you command me to leave (the world), Dear Jesus, then appear, o lover, to be embraced; show then yourself to me on the redeeming cross. |

* the most famous and – at the same time – most ‘shocking’ verse. It is not original (i.e. in the 13th century, this verse was not present). It was added only in the late 15th century. This does fit with the development of devotion, which in the 13th century was physical, sensitive, but remained focused on the fragile. In the late Middle Ages, the tone shifts, and the feelings raised become more straightforward, also rather emotional than sensitive/sensible. Paintings from this period also become increasingly sensational (à la Mel Gibson).

© Dick Wursten (2024)