Johann Heermann’s famous Passion song and the Meditationes of (pseudo-)Augustine.

Background to Herzliebster Jesu, was hast du verbrochen, the first chorale you hear when listening to the St Matthew Passion; two other stanzas also appear in it. In the Johannespassion the hymn is also represented with two stanzas. NB: Heermann did not claim to have written an original poem, but suggests that he put into metre and rhyme a Meditation of Augustine… Below the title he says: “Des Leidens Christi Ursach – aus Augustino” (About the cause of Christ’s Suffering – from Augustine).

The text

| Herzliebster Jesu (Johann Heermann, 1630) Des Leidens Christi Ursach – aus Augustino selection | Translation (Catherine Winkworth) |

|---|---|

| Herzliebster Jesu, was hast du verbrochen, Daß man ein solch scharf Urteil hat gesprochen? Was ist die Schuld, in was für Missetaten Bist du geraten? | O dearest Jesus, what law hast thou broken That such sharp sentence should on Thee be spoken? Of what great crime hast Thou to make confession, What dark transgression? |

| Du wirst gegeißelt und mit Dorn gekrönet, ins Angesicht geschlagen und verhöhnet, du wirst mit Essig und mit Gall getränket, ans Kreuz gehenket. | They crown Thy head with thorns, they smite, they scourge Thee; With cruel mockings to the cross they urge Thee; |They give Thee gall to drink, they still decry Thee; They crucify Thee. |

| Was ist doch wohl die Ursach solcher Plagen? Ach, meine Sünden haben dich geschlagen; ich, mein Herr Jesu, habe dies verschuldet, was du erduldet. | Whence come these sorrows, whence this mortal anguish? It is my sins for which Thou, Lord, must languish; Yea, all the wrath, the woe, Thou dost inherit, This I do merit. |

| Wie wunderbarlich ist doch diese Strafe! Der gute Hirte leidet für die Schafe, die Schuld bezahlt der Herre, der Gerechte, für seine Knechte. | What punishment so strange is suffered yonder! The Shepherd dies for sheep that loved to wander; |The Master pays the debt His servants owe Him, Who would not know Him. |

| O große Lieb, o Lieb ohn alle Maße, die dich gebracht auf diese Marterstraße! Ich lebte mit der Welt in Lust und Freuden und du mußt leiden. | O wondrous love, whose depth no heart hath sounded, That brought Thee here, by foes and thieves surrounded! All worldly pleasures, heedless, I was trying While Thou wert dying. |

| stanzas 1 ,2 ,3 ,4, and 7 (of 15). full text can be found here (original print) |

A hymn with a long history

In this hymn, the thoughts take their origin with Aurelius Augustine. Through a ‘personal reading’ of his texts (especially his sermons!), those thoughts deepen and condense with Jean de Fécamp (d. 1078, abbot of the Benedictine monastery La Trinité at Fécamp – Normandy), or one of his followers. They become a devout meditation on the question: ‘Why did Christ have to suffer in the first place?’ What is the cause (causa), and what purpose (finis). Yes, Anselmus with his ‘Cur Deus homo?’ is nearby, also geographically: in neighbouring Benedictine monasteries in Normandy: Fécamp and Bec-d’Hellouin). The answer to this question – in the idiom of the time: It is done ‘propter nos’ and ‘pro nobis’ (because of us, and for our benefit).

But beware: Augustine and Jean de Fécamp (and Anselmus!) do not practise theoretical theology, but existential theology. This insight comes from the inside (is the result of reflective introspection). It unmasks human pretensions (that he man can save himself, that everything will be all right if he only tries a little harder, that you only have to make sure you are on the right side, etc…), it makes man humble; and at the same time it elevates that same man: God apparently likes him – despite his obvious flaws – and even to such an extent, that He is willing to do everything for him: pro nobis, to our salvation and redemption. Jean de Fécamp had couched his meditation on this topic in a rhythmic prose text, that proved to appeal not only to his own monastic brethren, but is resonated thoughout Western Christianity. It was copied and circulated time and again. And while copying, his meditations were supplemented with fragments of similar meditations by Anselmus (also better: Pseudo-Anselmus, because no authentic works of this great theologian). By the end of the Middle Ages, some 39-41 meditations were circulating in Europe, often brought together under one heading: Meditationes Divi Augustini (Meditations of Saint Augustine).

The meditations of (pseudo-)Augustine

By then, the original author had been forgotten, and – as it is often the case – they are attributed to a person deemed capable of writing such great texts: Augustine (a circumstance that certainly didn’t harm their popularisation). When the printing press started working smoothly, they were printed, reprinted and translated, in large print runs. Both (Roman-)Catholics and Protestants continued to read, meditate, collect, make these texts their own, even after the ‘Western schism’ (the Reformation), and this well into the 19th century: spiritual ecumenism avant la lettre. The texts in this volume are thus personal meditations (prayers), introspective texts on God and man. Caput VII is thus about the suffering of Christ. They are indeed informed by Augustine c.s, and by hymns, prayer formulas and biblical texts. Jean de Fécamp wrote them in the first person singular. They therefore sound very personal (but make no mistake: this ‘I’ is not necessarily autobiographical; rather, it is didactic: Read these lines, and say after me,… and in doing so you are praying properly. They are, so to speak, the spiritual part of the monastic reforms taking place at the time (example: Cluny, St Bénigne in Dyon), meant to improve the inner life of the monks. After all, that was Jean de Fécamps’mission as an abbot. He could never have imagined that with these texts he laid the foundation stone of the meditation book of many centuries of Christians. You can hear passages and trains of thought when reading sermons by Marin Luther, or when you sing a spiritual motet by Josquin DesPrez, or Heinrich Schütz (in Latin and German), not only as far as Chapter VII is concerned. The prose texts from O bone Jesu also largely come from this book)… and so when we sing or hear Herzliebster Jesu. Below, for those who are interested, chapter VII (almost complete), as it appears in a 1755 printing (but this is based on a late 16th-century edition by Henri de Sommal (Sommalius). Also, the Protestant – Lutheran – version by Andreas Musculus, (Precationes, 1571, reprinted numerous times), does not change anything in this text.

Quid commissisti amantissime…

Caput VII (chapter 7) of this collection of meditations thus addresses the question of what caused Christ to suffer. After the quesion (section 1) and the answer (section2),. section 3 articulates the grateful wonder that God manages to put a positive spin on all this (the ‘joyful exchange’ Luther would say, some 350 years later). In the opening sentences of section 1, you easily recognise Johann Heermann’s song (the terminology that speaks of Jesus as a ‘lad’, ‘youth’ may come across as strange, but it was very common in pious devotions at the time: it ties in with the image of Jesus ‘as Son’ and emphasises his innocence, his vulnerability too. Emotional terms, like ‘sweet’ (dulcis, in Latin a very common term to name God’s loving mercy: Quoniam dulcis est Dominus tuus…)

Section 1 raises the question: why did Christ have to suffer in the first place? Full of paradoxes this section. You will recognise Heermann’s first 7 stanzas.

Section 2 brings out the insight that ‘I’ (ego) am the cause of it. The accumulation of short phrases calls, as it were, for a recitation, music.

Quid commisisti, o dulcissime puer, ut sic judicareris,

Quid commisisti, o amantissime juvenis, ut adeo tractareris?

Quod scelus tuum…

[What have you done wrong, o precious lad, that one condemns you like this,]?

[What have you done wrong, o dearest youth, that one treats you thus?]

[What is your sin?]

Johann Heermann and Johann Crüger

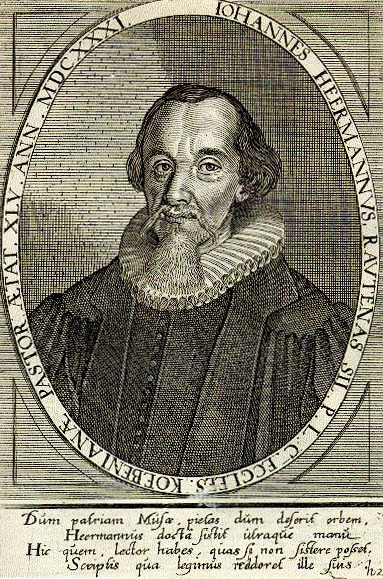

Johann Heermann (1585-1647) was apparently deeply affected and edified by this chapter and versified the Latin rhythmic prose into the song known to us. This must have been around 1630. He turned the meditation beginning “Quid commissisti, amantissime “… [What hast thou done wrong, dearest Jesus?] into a song of 15. Aside, five years earlier Heinrich Schütz had alreday set to music a selection of the Latin original – Cantiones Sacrae, 1625. See this page for that]. The metrical form chosen by Heermann covers the content: A Sapphic Ode:

– 3 long lines (11 syllables, caesura after 4 or 5 syllables, feminine rhyme) ;

– 1 short powerful sentence of 5 syllables.

He published the hymn in his collection of spiritual poetry:

DEVOTI MUSICA CORDIS. Hauß- und Hertz-Musica. Das ist: Allerley geistliche Lieder […] Durch Johann. Heermannum, Pfarrn zu Köben. Leipzig 1630. A

Above the song we read

Ursache des bittern Leidens Jesu Christi

und Trost aus seiner Lieb und Gnade: Aus Augustino.

Im Thon: Geliebten Freund, was thut jhr so verzagen? etc.

Johann Crüger composed the currently known melody (Heermann had only added a melody indication – see below) and gave it a four-part setting. In 1648 he included this in a (reprint of) his Praxis Pietatis melica (= very successful collection of spiritual songs, notated with b.c. for the domestic ‘Andacht’, hence the title: Musical spiritual exercises)

The same Crüger also included the hymn in his Geistliche Kirchen-Melodien from 1649 a text-critical edition of this can be freely downloaded on ISMLP (there no. 56, p. 124) – in addition to SATB also two additional voices (violins or cornets). The rest is history…

Via Bach’s Matthew Passion, this song is to this day the sound-evocation of the Good Friday event (even without lyrics). This along with that other hymn (by Paul Gerhardt O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden, also a song with deep roots in medieval piety. See this page for that).

The melody (how many flats?)

The melody is usually written down tonally in our days (with one flat, Liedboek 1973 – no longer included in Liedboek 2013), but is actually already a true minor melody (2 flats). This also renders the kinship wht or even dependence of – often reported by musicologists – the tune of the Geneva Psalm 23, dubious (Psalm 23 is truly hypo-doric, nor does it have the form of the Sapphic ode). The melody affects people precisely because within that metrical form, both text and tune work toward the short concluding phrase (climax).